Join us on Wednesday January 7 from 10 - 2 pm for the Opening Reception and Live Music

Exhibition statement

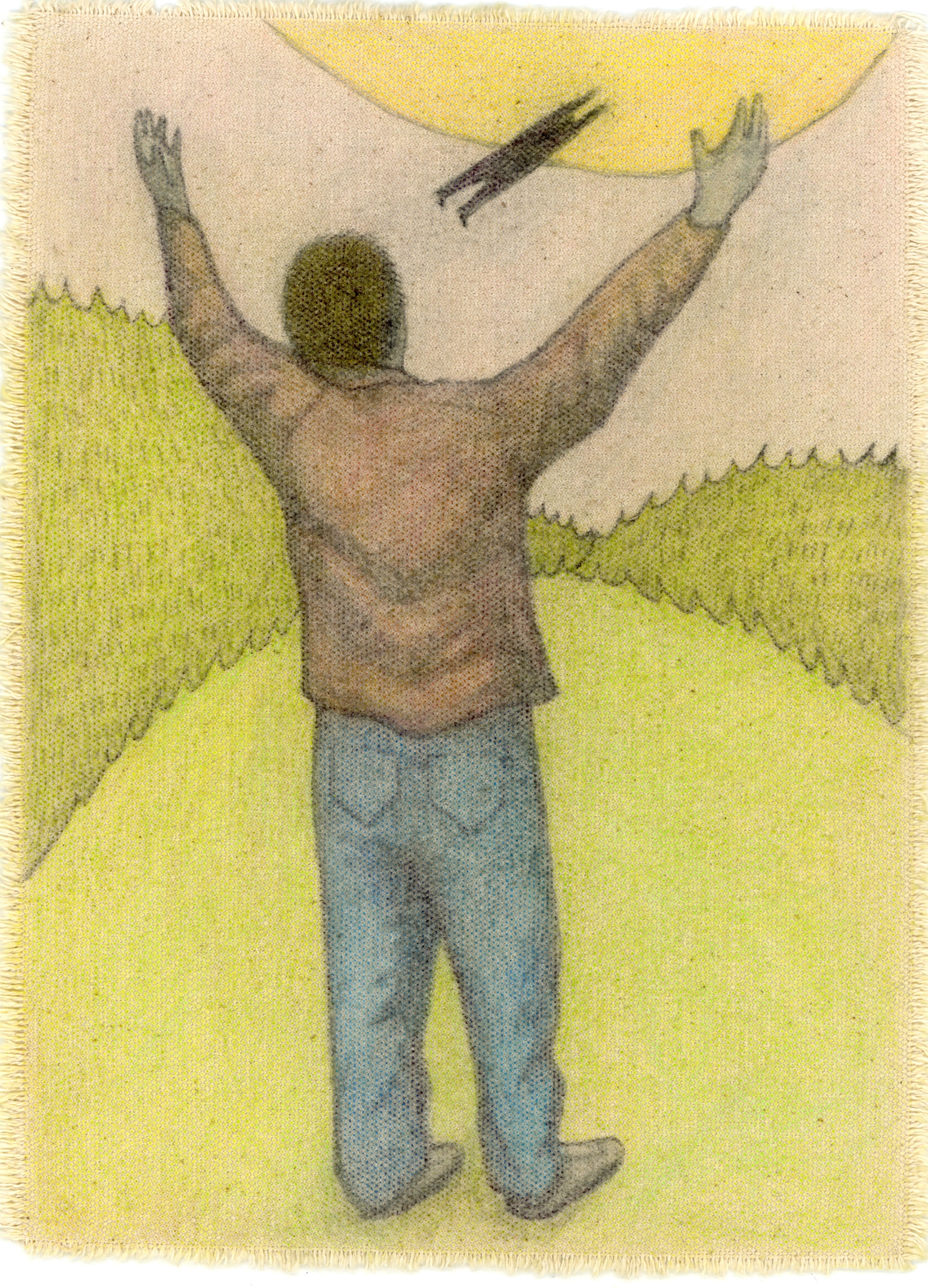

Country Fried gathers Kensey Kendall’s muslin drawings into a tender, rigorous meditation on the ethics—and the impossibility—of keeping. Born in 2002 in Michigan’s Northwoods and now working from Chicago, Kendall approaches image-making as a form of custodianship: a practice that does not simply preserve the past, but re-animates it, submits it to touch, and asks what it means to live alongside what is already gone.

The genesis of this body of work is itself an archival parable. In March 2022, Kendall received a mailed CD from Mesick Historical Museum archivist and curator Nancy Sanders—an informal, vernacular repository of donated photographs from rural Northern Michigan families. The disc, dense with “fuzzy figures in the bluest snowfall,” undulant hills, fish, and the irrepressible theater of smiling faces, stages a familiar contemporary dilemma: an excess of recorded life paired with an insufficiency of intimacy. These are images that appear to offer access, yet remain stubbornly ungraspable—portraits of a community that can be looked at but not held.

Kendall’s intervention is neither illustrative nor restorative; it is translational. Rendering photographic remnants into pencil on cloth, she converts the archive from a static container into a living proposition. The muslin—porous, domestic, bodily—rejects the hard neutrality of institutional storage in favor of a surface that behaves more like skin than paper. In this register, drawing becomes a durational encounter: the slow insistence of attention replacing the camera’s instantaneous capture. Kendall’s hand does not “recover” these figures so much as host them, allowing them to accrue presence through labor, repetition, and proximity.

What emerges is an intimate choreography between past and present that complicates the archive’s claim to objectivity. Kendall “compartmentalizes the one we’re living in into its own,” not to separate history from now, but to establish a permeable border where dialogue can occur. The depicted faces—silly, straight, familiar without being known—are treated as interlocutors rather than subjects. Through this relational stance, Country Fried proposes memory as something made, not found: an actively negotiated space in which story and symbolism operate as technologies of care.

At stake here is the paradox Kendall names directly: a desire to “keep things that can’t be kept.” The work acknowledges that preservation is always partial, always haunted by loss; yet it refuses cynicism. Instead, Kendall offers a counter-logic of commitment—an insistence that to draw is to remember with one’s whole body, to make room for others inside one’s own temporal frame. In Country Fried, the uncollectable is not conquered; it is courted. These drawings do not promise permanence. They propose, more quietly and more radically, a practice of being with: of holding what cannot be held long enough to feel its human weight, and to let it alter the present.